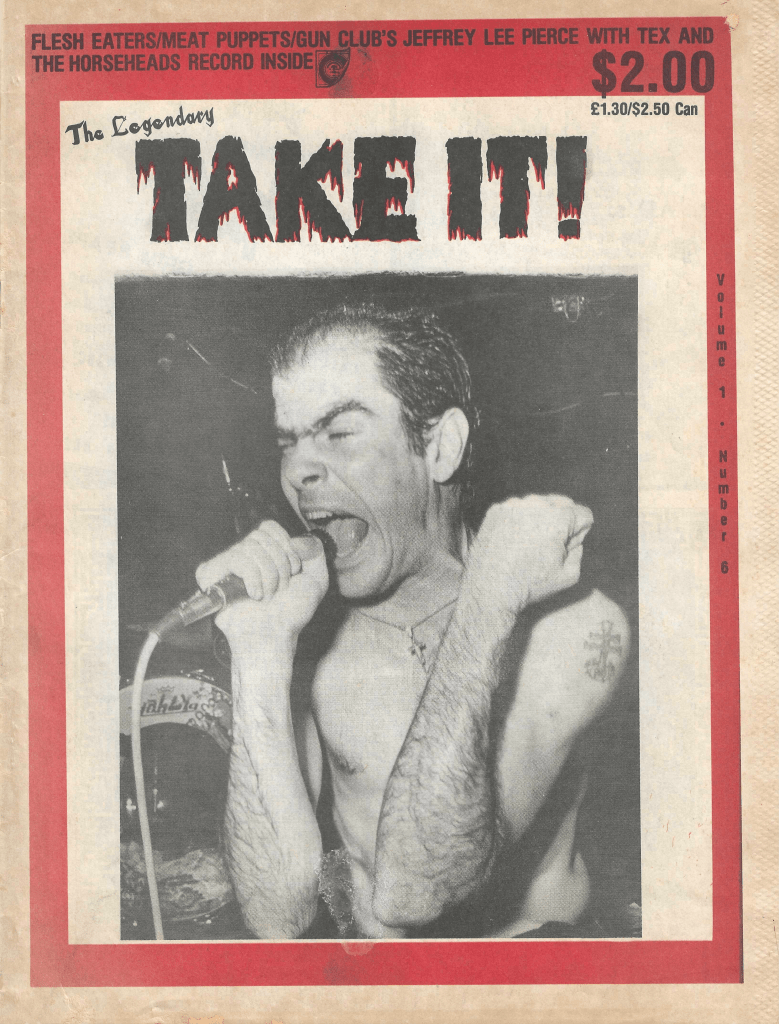

Finally, we wrap up the Fanzine Hemorrhage project, which has been running constantly & with a couple hundred reviews written since 2022, with what’s likely my favorite issue of any fanzine, ever. It’s Take It #6 from 1982. But first, a couple of things:

- I put out my own fanzines in the 2010s and 2020s under the names Dynamite Hemorrhage and Radio Dies Screaming. The ten issues of the former are now sold out, but I have plenty of issue #1 of the latter, from late 2024. Take a look, and feel free to order Radio Dies Screaming #1 here.

- For years, I’ve taken photos of old American signs – mostly motels and faded glories of the 1950s and 1960s. I mean, it’s not at all professional or anything – they’re phone photos – but I’ve got an, um, ongoing “portfolio” here if you’re interested. I’m not on social media, so this is kind of the only way I’ll likely get anyone to ever take a peek.

- I’ve got an eBay page set up to unload some extraneous fanzines, and other printed matter that I’m now done with. I’d love for you to take a look and bookmark the site if you ever like to buy old music fanzines and/or collected ephemera from the past. It will be updated frequently. Check it out.

Now, let’s talk about Take It #6.

This is the lone issue of Take It! that I can say I was “contemporaneous” with; I distinctly remember it being available for purchase at the Record Factory on Blossom Hill Road in San Jose, CA, but I also remember not buying it, given my non-familiarity with the bands on the flexidisc – oh, just The Flesheaters, Meat Puppets and Tex and the Horseheads, each at the height of their respective powers. “The greatest flexidisc of all time”, some have called it (actually that was me that called it that). Anyway, I’d get my copy a few years later while I was in college, and I’ve savored it like a fine chianti with fava beans for years. As long as we’re making lists, it’s one of the single best issues of a fanzine that I’ve ever encountered as well.

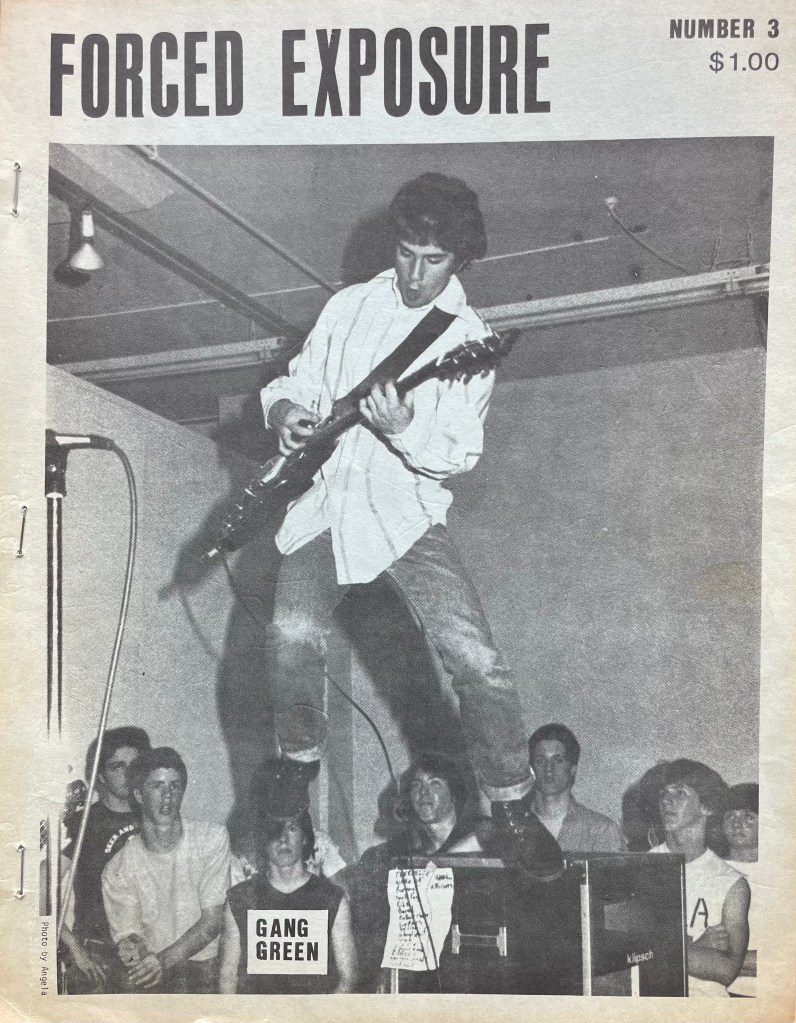

I’ve probably read it more times than anything save my Forced Exposures, but until today it had been a while. Opening it now to tell you about it, I’ve found that Michael Koenig writes in the intro that he patterned the cover of this magazine to be much like that of Slash, given that Chris D. of the Flesh Eaters (who wrote for Slash) is the cover star. Ironically, this issue of Take It! has shrunk to a normal 8.5”x11” size after having been the jumbo tabloid size of Slash for every issue before this final one.

But wait – let’s talk about that flexidisc first. Tex and The Horseheads with Jeffrey Lee Piece do a blitzkrieg version of “Got Love If You Want It”. While this is not the first band I might go to for the full “roots/punk” experience, I kinda think they’re a bit underrated, and they capture a side of LA that I got to see myself in late bloom five years later: the jean-jacketed, longhaired, alcoholic, wasted sleazoid faux cowboy punk that haunted Hollywood Blvd. and clubs like Raji’s. The Meat Puppets, at the height of their powers, contribute “Teenager(s)”, which I’ve written about elsewhere as having the best opening two seconds of perhaps any song, ever, before turning into a shitstorm of nonsense, and then into a laid-back hippie/doper desert mind-expander. (Check Dynamite Hemorrhage #5 if you want to read more about it). And a live Flesh Eaters track (!), “River of Fever”, was recorded on the 1982 tour that Byron Coley writes about in this issue, about which more later.

The mag starts off with a great “three dot” gossipy column by one Julie Farman – who’d go on much later to detail a sexual harassment incident with the Red Hot Chili Peppers she was the victim of – called “Blabbermouth Lockjaw”. She gives some great copy about T.S.O.L. trying to beat up Minor Threat’s Brian Baker in a bathroom; a near-death accident in Boston when Snakefinger’s “Snakemobile” flipped over; a never-was 80-page Byron Coley fanzine called Flunk that’s “about to come out”; and – ooh, ouch, “Fear replaces Derf Scratch with something/one called THE FLEA”.

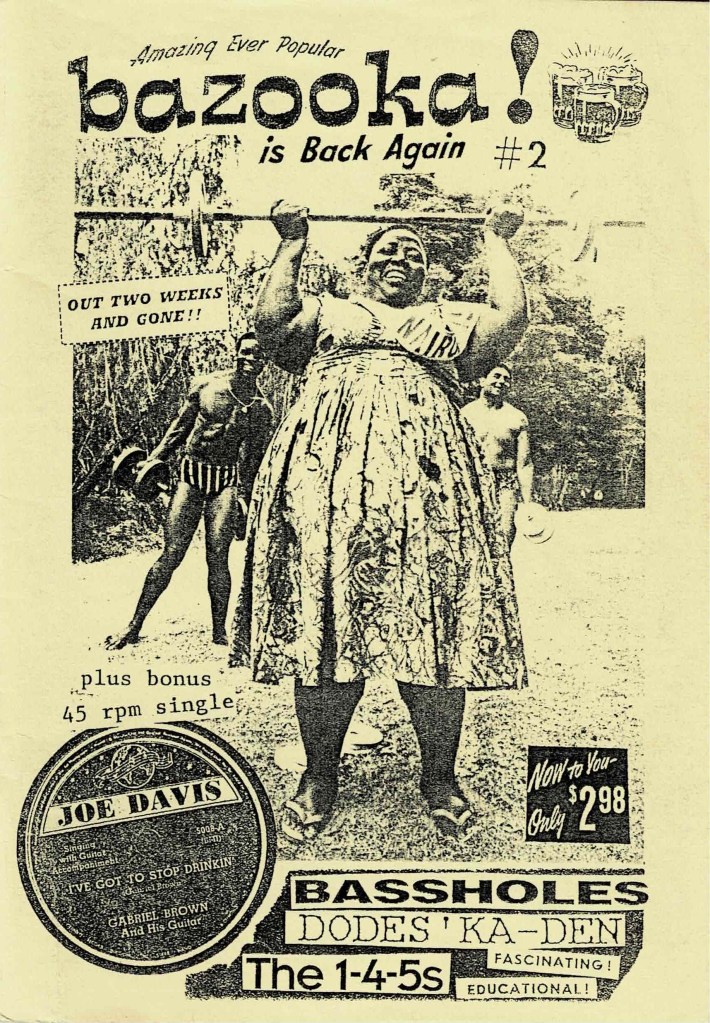

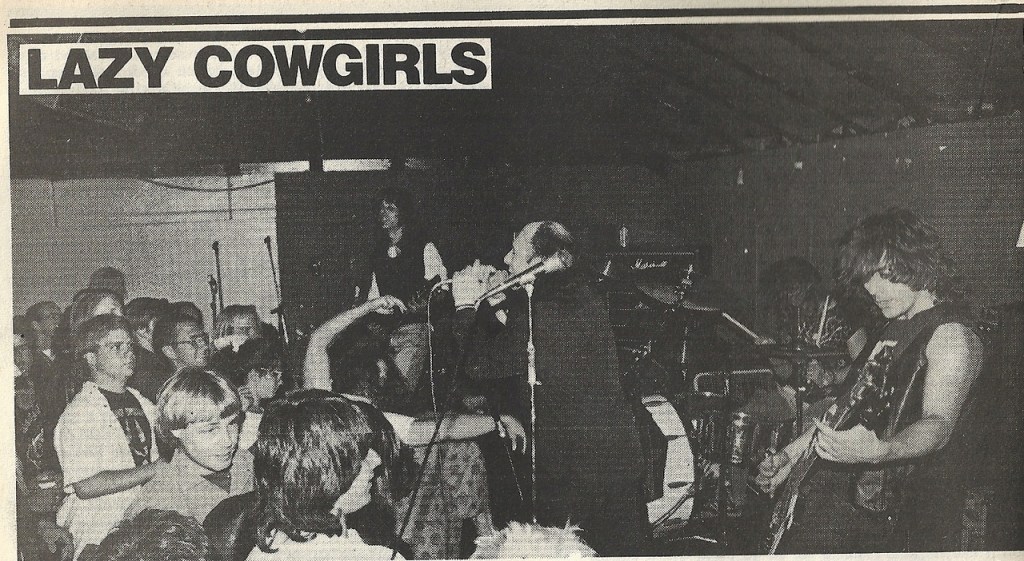

Michael Koenig gives his own Boston live action scene report and makes me wish I’d seen Talia Zedek in Dangerous Birds; David & Jad Fair in Sit: Boy Girl, Boy Girl, and Chris D. in the Flesh Eaters (well, I did see that, but not until 1990). Chris D., in fact, gets his own column in here – was this his first published writing since Slash went under? Someone’ll have to tell me. One of the true standout columns this time is a new one from Don Howland, whom you perhaps know from his later work with the Gibson Bros and the Bassholes. Here he dissects the musical sins of Australia, and counts down a “Low 11” of insipid pop acts that I still quote from to this day.

The piece that always really did it for me in this one is Byron Coley’s tour diary of his time roadie-ing for The Flesh Eaters on their first national tour – “Flesh Eaters ‘82: Masterpieces Hexed from the Dunes of Jive Broken Roads” (sounds like Chris D. might have titled that one). For years, and perhaps even now, I’ve claimed the 1978-83 Flesh Eaters as “my favorite band” – and also for years, this was the most up-close-and-personal I’d ever gotten with them, all filtered through Coley’s mania for the American underground and his warped sense of humor. The part about them playing live in Madison with Die Kreuzen always made me pretty jealous; in fact this whole tour they’re mostly playing with hardcore bands, forcing the band to play faster just to keep the pits flying. You can actually hear it on “River of Fever” on the flexi, which turns into a breakneck pace midway through, quite unlike the version on A Minute to Pray, A Second to Die.

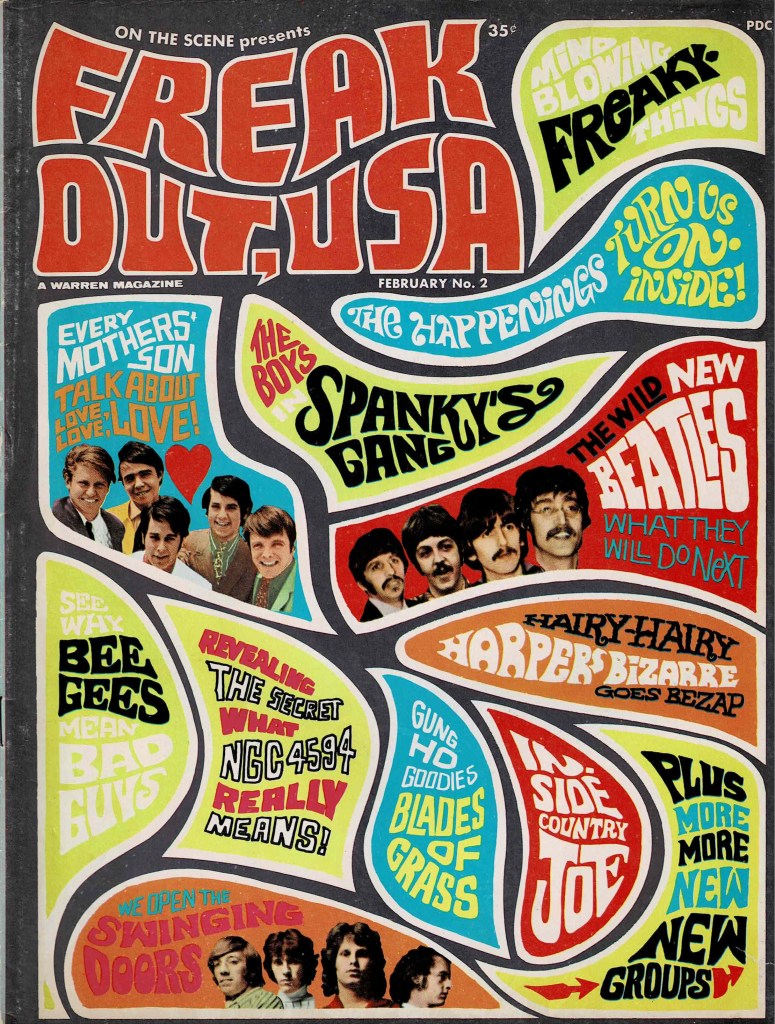

Other highlights – Gregg Turner turns in an excellent LA scene report, complete with absurd reprinted lyrics from a local metal band called Slave-State whom I’m very sad to report did not appear to ever get any vinyl released. Eric Lindgren writes a piece about “The 10 Most Twisted Tracks From The Sixties”, including The Lollipop Shoppe, Legendary Stardust Cowboy, MC5 and Swamp Rats. Byron Coley writes an insane amount of record reviews, plus a column on beatniks. Richard Meltzer and Mick Farren have their turns as well. And….that’s it. That was the end of Take It!. No pleas for financial help, no indication that another issue wasn’t around the corner, nothing. The magazine gathered steam and rapidly got stronger and when it died with the publication of this issue, it was easily the best fanzine in the USA.

Even today – in 2026 – every single issue is available directly from Michael Koenig himself right here. Fair warning: it’ll cost you, especially #6, which, at $250, is 10x the price of each of the others. I’d wait for your Hanukkah or Christmas money to accumulate, and maybe write Koenig a nice email and see if he’ll sell them all to you for <$300. Tell him Jay at Fanzine Hemorrhage sent you. And thanks for reading!